COVID-19 and Chloroquine: FDA Authorizes Use, But Risks Persist

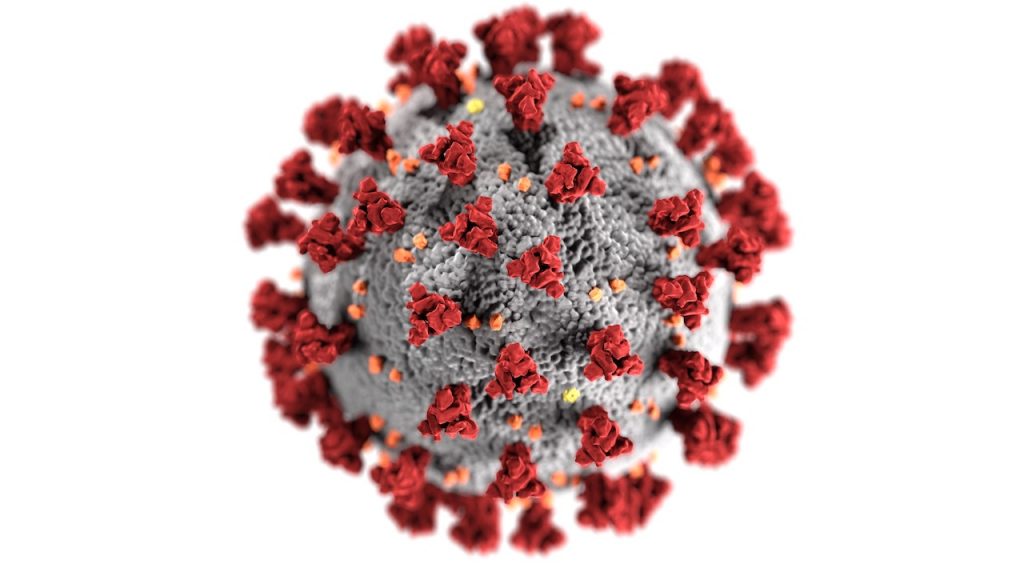

The FDA has authorized emergency use of anti-malarial drug to treat novel coronavirus. The medical director at the Michigan Poison Center says it comes with risks.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has issued an emergency authorization to use chloroquine and hyrdoxychloroquine to treat patients with COVID-19, the disease caused by the 2109 novel coronavirus.

In a letter to the Department of Health and Human Services, the FDA’s Chief Scientist, Rear Admiral Denise Hinton, wrote that the potential benefits of treatment with these drugs outweigh the potential risks. She based that conclusion on “limited in vitro and anecdotal data” available from use of the drugs in other countries, and the fact that the novel coronavirus has created a national public health emergency.

“Ideally, nobody should take this drug unless somebody can run a drug interaction profile on them.” — Dr. Cynthia Aaron, Michigan Poison Center

The letter outlines specific circumstances in which chloroquine and hyrdoxychloroquine may be administered to COVID-19 patients.

Some doctors were already prescribing the anti-malarial drugs before the FDA’s letter was released on March 29, 2020. But whether it turns out to be reliably effective or safe remains to be seen.

“No Good Evidence”

Chloroquine has been used for decades to treat malaria. A similar drug, hydroxychloroquine, is commonly prescribed for patients with lupus, rheumatoid arthritis, and other conditions.

Clinical trials are underway to determine if these are effective treatments for COVID-19. But until those tests are completed, physicians warn against calling it a cure yet.

“There’s no good evidence at this point, no good randomized control trials to show that it will make a difference,” says Dr. Cynthia Aaron, medical director of the Michigan Poison Center at Wayne State University’s School of Medicine.

Aaron says chloroquine and hyrdroxycholorquine did show some promise in treating people with severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), which is also caused by a strain of coronavirus.

“But to say that there’s irrefutable evidence that it’s effective at this point, that just doesn’t exist,” Aaron says.

By contrast, there is evidence that taking too much of either drug, or mixing them with other medications, can be harmful — even fatal.

Aaron says exceeding the recommended therapeutic dose is dangerous.

“If you go twice that therapeutic dose, you’re going to be sick,” Aaron says. “You may end up in the hospital. You could even end up on a ventilator, having heart arrhythmia. And if you take three times that dose, you’re dead.”

Deadly Combinations

Both drugs also have a number of negative interactions with a host of other types of medication, including some opioids, heart medications, and antibiotics.

“Ideally, nobody should take this drug unless somebody can run a drug interaction profile on them,” Dr. Aaron says.

Some have advocated using hydroxychloroquine with azithromycin, a common antibiotic. But so far, those recommendations have been based on tests involving a handful of patients, including some in France who responded well to the treatment.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says combining hydroxychloroquine and azithromycin can prolong the time it takes for the heart muscle to recharge between beats, a condition known as QT prolongation. The CDC advises caution in using the two drugs in patients with chronic medical conditions.

The agency also warns against using non-pharmaceutical chloroquine phosphate, which is commonly found in aquarium cleaners.

Aaron says anyone who experiences symptoms such as nausea or vomiting after taking chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine should call a poison control center immediately.

The Michigan Poison Center’s number is 1-800-222-1222.

Click on the player to hear Pat Batcheller’s conversation with Dr. Cynthia Aaron, and read a transcript, edited for clarity, below.

Pat Batcheller, 101.9 WDET: What are chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine and how are they used?

Dr. Cynthia Aaron, Michigan Poison Center: Chloroquine was originally derived from the bark of the Cinchona tree, which lives in the tropics. It was noted by the local people that, if they chewed on the bark or made a decoction of it, that it helped treat periodic fevers. Those fevers were eventually determined to be malaria.

It is still used to treat malaria, but only specific types, because the malarial parasite (Plasmodium) has become resistant to chloroquine. Deadlier forms of malaria, such as falciparum, are treated with other drugs.

Hydroxychloroquine is a slight tweak. Right now it is used almost exclusively for lupus and for people with dermatomyositis and rheumatoid arthritis. It does have some immuno-modulating effects, which is why some are looking at it [for COVID-19].

Why are some doctors prescribing these drugs to treat COVID-19?

When this started out, everybody did a mass search for anything out there that might be useful. There is some earlier evidence that chloroquine and hydroxychloroquine may have been useful in the SARS coronavirus outbreak, and that’s what triggered their approach to start using it.

There are a couple of mechanisms that look interesting, when you look in a test tube or cell culture, about the way that it prevents binding of the virus to the to the cells and alters the way it works in the cell.

But there’s no good evidence at this point, no good randomized control trials to show that it will make a difference in people with COVID-19.

The concern is there are a lot of drugs that look very interesting in vitro. And I think there’s something like 80 clinical trials going on, which suggests that nobody has a great answer. But it’s only one of many drugs that they’re looking at.

It is readily available, and because it is an FDA-approved drug for malaria, lupus and rheumatoid arthritis, it can be used for other things.

But to say that there’s irrefutable evidence that it’s effective at this point, that just doesn’t exist.

China, where the pandemic began, is conducting clinical studies on combining hydroxychloroquine with the antibiotic azithromycin. That could be deadly, though, couldn’t it?

Yes. The problem with these drugs is that for the diseases that are being treated, they are effective at a what we call a therapeutic dose. These drugs are profoundly dangerous, in that, if you go twice that therapeutic dose, you’re going to be sick. You may end up in the hospital. You could even end up on a ventilator, having heart arrhythmias. And if you take three times that dose, you’re dead. So we don’t recommend that.

The other issue is — and the really bigger one for the doctors in the hospitals — is that these drugs have a slew of interactions. And the way the body metabolizes the chloroquine class is through a group of enzymes, called the CYP enzymes (Cytochrome P450).

If you have someone on a drug that competes for that same enzyme system, one of those drugs is going to increase in concentration and lead to toxicity.

And because the enzymes that are involved are very common for some antibiotics, opioids and a bunch of other drugs, the risk of having these very sick patients on these drugs increases the risk that the blood concentration of the chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine is going to increase significantly.

On top of that, these drugs are cleared from the body through the kidneys. COVID-19 hits the kidneys, and they don’t function as well. And so you can accumulate the drug that way.

Who should not take these drugs?

Anybody who has a heart condition. Anybody who has a conduction abnormality – a slow heart rate or a rate that speeds up. People who are on certain antibiotics such as Levofloxacin or that class of drugs. Anybody who is taking Amiodarone for their abnormal heart rate. Anybody who’s on an opioid such as buprenorphine. There are some antidepressants that come into this.

Ideally, nobody should take this drug unless somebody can run a drug interaction profile on them. If they have a history of lightheadedness, dizziness, they should not take it. If they have kidney disease, they should not take it.

What else should we know?

If you decide to do this — which I don’t advise without a doctor’s supervision — then if you get any nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, light-headedness, tremors, can’t think straight, hallucinate, have feelings like you’re going to pass out, you need to either immediately call the Poison Center or seek medical care. When the toxicity hits, it is a sudden and severe cardiac toxicity.

There is also a severe shortage of the drug right now. And people who need it for their diseases, particularly someone who has lupus, it may be life-saving.

There is no good evidence to show that that taking it prophylactically or with mild symptoms is going to change anything. I just would recommend not doing it.

If you’re in the hospital, you may then be involved in a clinical trial or under a controlled situation where they can be watching for those drug interactions, and then that’s up to the purview of the physician treating you.